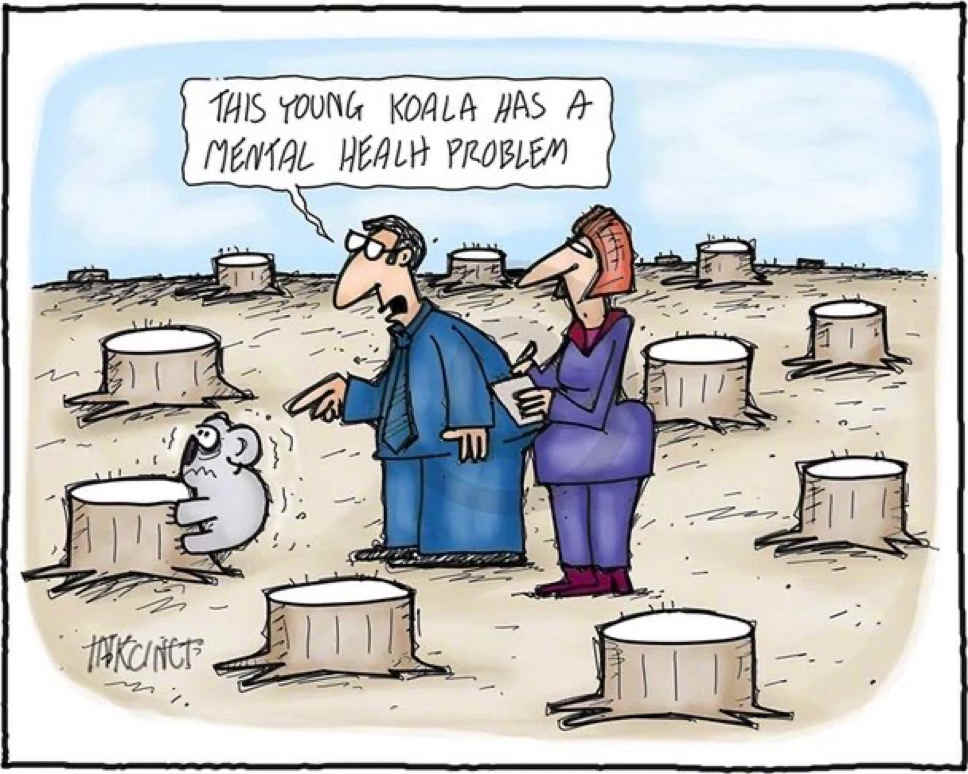

The ‘mental health crisis’ is a misnomer. When people are troubled it's often not the case that people have something internally wrong or different in them, but rather that they are not properly embedding themselves in the external world. We all have biological and psychological particularities that make us special and different ― and it is true that a few of these particularities can be constructively analyzed and then categorized for a better insight of our inner workings. But reducing ourselves entirely to the biological-brain ― or even the psychological-mind ― takes away from understanding our higher-level social integration that frequency sheds a much better light on why-and-when we become maladaptive.

Psychiatry is inward and reductionistic in its approach. It focuses on the lower-levels: hormones, drives, feelings and thoughts. It often leaves out the strong possibility that maladaptive seen is likely to be symptoms of higher-level socialization problems that people are facing ― the greater number of individuals not having a strong friend/family network being a major one. The ‘mental health crisis’ is likely not something that can be fixed by a lower-level manipulation of thoughts, hormones and body parts.

Psychiatry in its current form over-classifies. Some of the introduced terminology in psychiatry is helpful in that it generalizes ‘root causes’ and ‘emergent behavior’ (things that cannot be reduced to a sum of the symptoms) from observing a cluster of symptoms together that have something in common with one another. But there is also a large amount of terminology in psychiatry that clusters symptoms together without the symptoms having an underlying connection. Much of the terminology in psychiatry is redundant being of the second sort.

When we group symptoms together in a name some people start to adopt the name as a identity signifier. Individuals that adopt the label sometimes then start to believe that they have all of the listed symptoms of said label, even if they had no history of such symptoms in the past. Principal of imitation ― people add to their stories from stories they are exposed too. Let's call this behavior as being part of ‘Placebo Effect’ or the ‘Scully Effect’ if we want to use modern midwit academic terminology. Though even the educated of the middle ages understood that madness is largly a spreadable disease. Letting people adopt their psychiatric diagnosis as their star sign is actively counter-productive at preserving sanity.

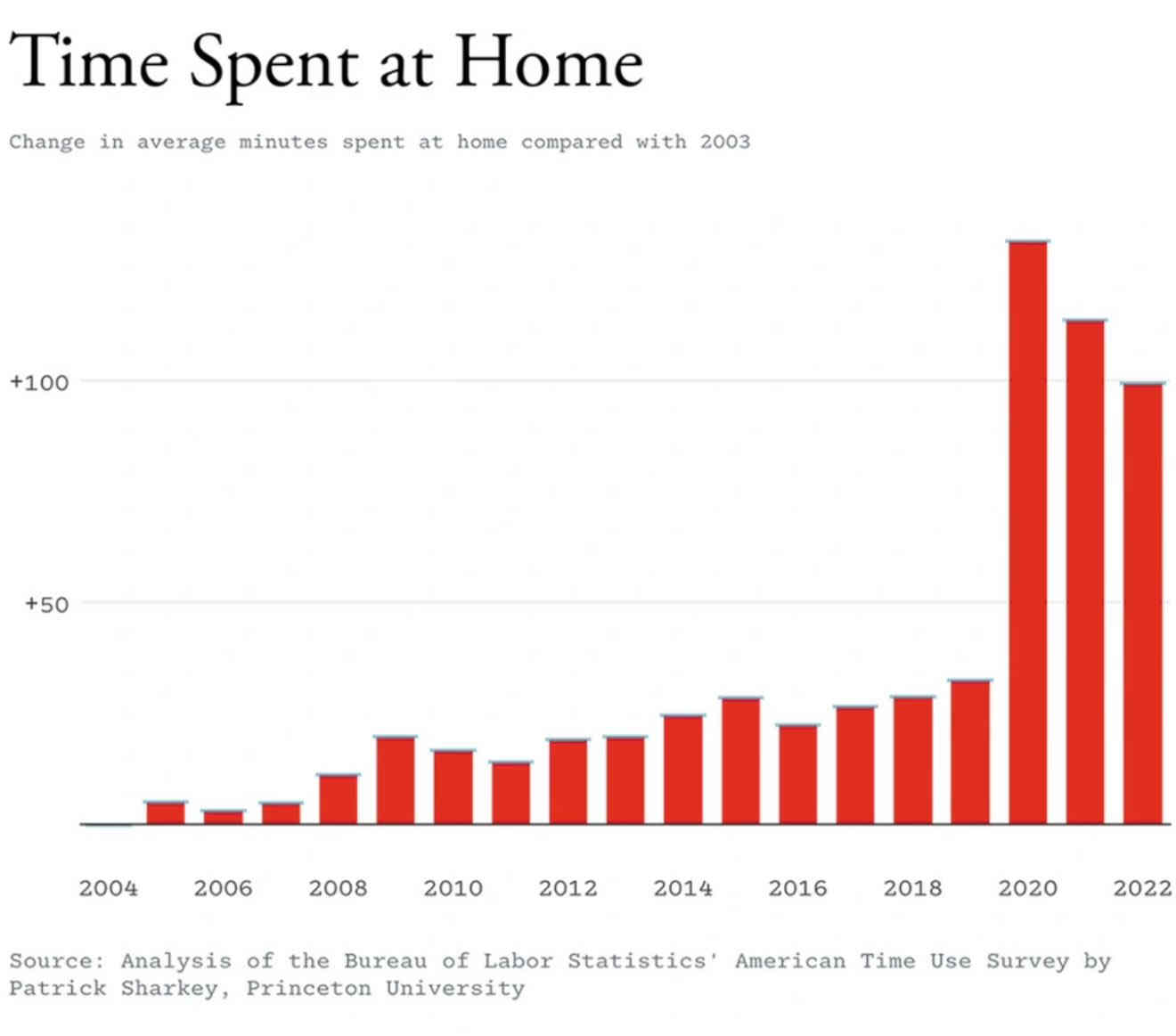

To solve the ‘mental health crisis’ we should be more holistic and general in our approach. We should encourage people to externally participate in the world over trying to analyze and categorize the internal workings of the individuals within it. Being properly tied to the earth and ‘going though the motions’ of participating in it is where individuals find meaning and is where many inward mental troubles eventually fall away from. The ‘mental health crisis’ is largely a sociocultural phenomenon.