The Spiritual World

JULES I just been sittin‘ here thinkin‘.VINCENT About what?

JULES The miracle we witnessed.

VINCENT The miracle you witnessed. I witnessed a freak occurrence.

JULES Do you know that a miracle is?

VINCENT An act of God.

JULES What’s an act of God?

VINCENT I guess it’s when God makes the impossible possible. And I’m sorry Jules, but I don’t think what happened this morning qualifies.

JULES Don’t you see, Vince, that shit don’t matter. You’re judging this thing the wrong way. It’s not about what. It could be God stopped the bullets, he changed Coke into Pepsi, he found my fuckin‘ car keys. You don’t judge shit like this based on merit. Whether or not what we experienced was an according-to-Hoyle miracle is insignificant. What is significant is I felt God’s touch, God got involved.

― Dialogue between Jules (right) and Vincent (left) in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction

Modern science appears to have given us an incredibly detailed map of the world, but closer inspection reveals surprising blind spots and gaps. Questions like why subjective consciousness arises at all or if all miracles can be accounted for seem to lie outside mechanistic descriptions of nature. These questions inherently cannot be reduced to current physical laws and our empirical experience with them often undermine our neat mechanical narratives about the world .

The Hard Problem of Consciousness

One famous blind spot for mechanical descriptions of the world is subjective experience. We can describe how neurons fire and how an animal behaves, but why these physical processes are accompanied by “what it is like” to feel, see red, or taste sweetness remains mysterious. Philosophers call this the “hard problem of consciousness”. Even if we fully explain all functional and structural brain processes, we can still meaningfully ask why is it conscious?”, suggesting that an explanation of consciousness may need something beyond standard science.

There is an unbridgeable gap: a complete physical account of the brain could leave unanswered whether the creature is conscious at all. We can even coherently imagine a creature physically identical to us that lacks any subjective feelings. This indicates that purely structural explanations omit the “what it’s like” of experience, the qualia, creating an irreducible divide between description and experience.

Treating thought as symbol manipulation makes sense for behavioral functions but it does not, on its face, explain why those functions should carry a first-person feel. Neural imaging and brain scans reveal correlations (patterns of voltage, activation, and circuitry), but they never capture the inner, qualitative character. A brain scan might detect the color “red” in the visual cortex, but it cannot render the redness itself; it only shows voltages, not the phenomenal quality of red. In this sense, consciousness behaves like evidence of something beyond the physical realm..

Conciousness has only be described through first-person experience. Treating consciousness as describable through mechanical explanations is not truthful.

Holes in the Laws of Nature are Often Not Acknowledged

David Hume famously defined a miracle as an event that violates “laws of nature”. He reasoned that our uniform experience establishes some models of the world so firmly that any single contrary event is a harder story to swallow than to doubt the eyewitness. He argued that because we have never observed, say, a dead person returning to life, “firm and unalterable experience” provides what he calls a full proof against any miracle occurring. Hume concluded, in effect, that no testimony should be believed unless the lie in the testimony would itself be even more miraculous than the event claimed.

This calculus treats things that go against law of nature as impossible: if someone observes a violation of law of nature, we weigh the established law against the fallibility of the witness, and always assume error, hoax, delusion, or a miscalculation over a violation of law of nature. This is circular logic: Hume’s argument is that violations of the laws of nature never happen … because they never happen.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s famous “Turkey Problem” illustrates the danger of Hume’s inductive certainty. In the problem each day a turkey observes benevolent treatment and its confidence in “farmers love turkeys” grows stronger. Yet on Thanksgiving the farmer kills the turkey: from the point of the view of the turkey an unforeseen high-impact event (e.g. a black swan event). This parable highlights that even one ‘miraculous’ event that has no president can overturn observable trends.

Hume’s argument against miracles is not an effective argument of why miracles can’t happen, but only an argument against giving credit to miracles due to their rarity. Hume’s inductive certainty did not serve the turkey well: just because the turkey survived up to Thanksgiving did not mean it would survive Thanksgiving. Just because observation of the past points against miracles occurring due to their rarity does not mean that miracles can’t happen or are an irrelevant feature in the world. Miracles as exceptions to the laws of nature cannot, by definition, be reproduced in a regular and reliable fashion: just as black swan events cannot be reproduced in a regular and reliable fashion.

Holes In the Laws of Nature, if Acknowledged, Often Lead Only to Superficial Modifications of law of nature.

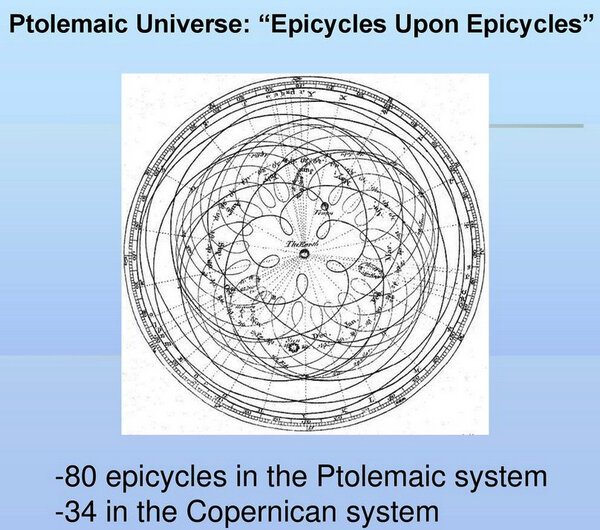

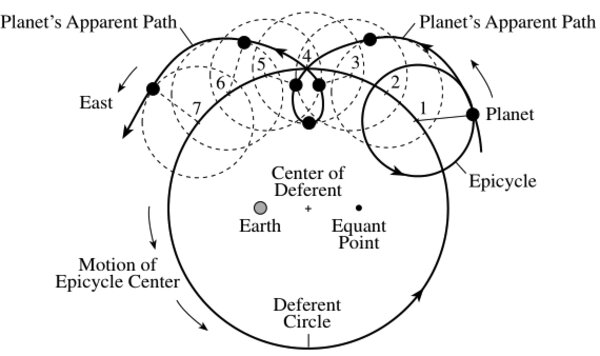

For nearly two millennia the Ptolemaic, geocentric cosmos reigned supreme. When planetary positions deviated from prediction, ancient astronomers did not discard geocentrism; they simply added epicycles, smaller circles riding on larger circles, to retain their understanding of the laws of nature. By the late Middle Ages the model contained dozens of such ad-hoc devices, each preserving the Earth-center and postponing a conceptual revolution. Even Nicolaus Copernicus, who placed the Sun at the centre, initially retained many of these circles because his deeper commitment to perfectly uniform motion remained unchallenged. Only after Kepler introduced elliptical orbits, and Newton supplied a new dynamics, did astronomy finally abandon epicycles altogether.

For nearly two millennia the Ptolemaic, geocentric cosmos reigned supreme. When planetary positions deviated from prediction, ancient astronomers did not discard geocentrism; they simply added epicycles, smaller circles riding on larger circles, to retain their understanding of the laws of nature. By the late Middle Ages the model contained dozens of such ad-hoc devices, each preserving the Earth-center and postponing a conceptual revolution. Even Nicolaus Copernicus, who placed the Sun at the centre, initially retained many of these circles because his deeper commitment to perfectly uniform motion remained unchallenged. Only after Kepler introduced elliptical orbits, and Newton supplied a new dynamics, did astronomy finally abandon epicycles altogether.

Modern science is no less susceptible to epicycle-making. When a black-swan level observation revealed that galaxies recede ever faster from one another, cosmologists introduced dark energy, an invisible cosmic repulsion, to salvage general relativity at cosmic scales. When galaxy clusters rotated too rapidly to remain bound, astrophysicists posited dark matter: another unobservable entity that supplies the missing mass. Black-hole information paradoxes are handled by ever subtler conjectures about quantum “firewalls" or holography. And when the two great frameworks of physics (general relativity and quantum mechanics) refuse to mesh, theorists add layers of mathematical machinery (string‐theoretic dimensions, loop-quantum lattices, etc.) rather than declare the prevailing paradigms inadequate.

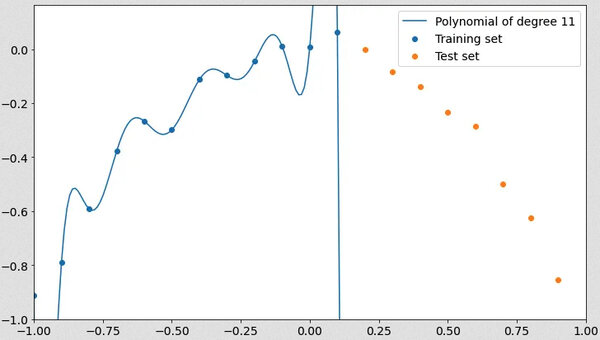

In the language of statistics, science is overfitting when adding these types of ad-hoc complexities — stretching a curve so artfully that it passes through every known point while forfeiting its power to predict the next one. Instead of stepping back to search for a new equation, we adjust coefficients, introduce hidden variables and raise the polynomial degree, all to keep the existing form intact. Instead of looking for a new paradigm in physics in response to an unexpected observation, we add in new complexity to existing models without challenging the fundamental assumptions.

In the language of statistics, science is overfitting when adding these types of ad-hoc complexities — stretching a curve so artfully that it passes through every known point while forfeiting its power to predict the next one. Instead of stepping back to search for a new equation, we adjust coefficients, introduce hidden variables and raise the polynomial degree, all to keep the existing form intact. Instead of looking for a new paradigm in physics in response to an unexpected observation, we add in new complexity to existing models without challenging the fundamental assumptions.

Our materialistic models of the world do not give us as a complete view of the world as they first appear to. They often provide ad-hoc explanations to new observations in a epicycle making manner to preserve their all-encompassing facade .